We start to think about what else we want to do in our last day in Kyoto. We fly out to Korea tomorrow and then on to London. We have a job in Stoke on Trent to build one of our small-scale, fuel-efficient wood fired kilns for the new ‘Clay College’ that has started up there this year.

I decide that I will go back to the Aizenkobo indigo workshop and buy a jacket. I have been carrying the image with me of trying it on now for the whole time that we have been in Japan, as it was the first place that we visited when we arrived. I have chosen a hand dyed indigo, hand-woven, hand-made, tight, dense, cotton fabric, jacket. It’s more expensive than I have ever paid for any piece of clothing in my life at $300, but you only live once, so here goes. I really like it.

We arrive in Seoul and the first thing that I notice are the carpet tiles in the entrance area at the airport. I’ve been here a few times before, but I haven’t noticed them previously. Imitation indigo nylon carpet floor tiles. It’s the perfect segue from our indigo adventures in Japan to Korea.

Miss Kang has given us a present of some special fermented tea from Jeju. Korea has an island to its south called Jeju island. It is a volcanic island and therefore the weathered basalt soils are very rich and fertile. It has elevated slopes that are just right for the cultivation of tea. Being south of the peninsula, it is sub tropical and warmer than the mainland, but being quite elevated, the higher slopes are cooler at night. Apparently it makes for an ideal tea growing climate. There is one particularly large tea plantation that draws all the tourists that visit the island. They grow several cultivars, each one specially suited to each specific soil type, aspect and micro climate.

Miss Kang has chosen for us a particular blend of fermented black tea, that is very mild and low in caffeine. It is processed, fermented, dried, but then re-moistened with steam and pressed into little bricks, then re-fermented and aged up to 100 days in what is described as a Post-fermentation process. Each finished little brick is individually wrapped and the whole lot packaged in tray that is then packaged a very impressive presentation box.

It’s really beautifully done! The packaging is certainly very impressive and the flavour of the tea is very mild, low in acid with a distinctive aroma. I haven’t come across anything quite like it before.

The little individually paper wrapped tea leaf brick is impressive. I like it. It swells up into a pot full of fully formed tea leaves. I have read about ‘brick’ tea in the past, but never actually come across it. It’s a particularly asian thing. As I understand it, ‘Brick’ tea, or blocks of pressed, dried tea leaves were used as a form of currency in China and also throughout parts of Southeast Asia in time past. It was light to carry, easily stacked and packed and could even be crumbled apart and eaten to get a bit of a buzz to keep the labourers going on long treks. There is a rather long listing on wikipedia about brick tea, particularly in regard to the tea trade from China up into Tibet.

I thought that I had better enlighten myself, so I downloaded this quote from Wikipedia;

Ya’an is the main market for a special kind of tea which is grown in this part of the country and exported in very large quantities to Tibet via Kangding and over the caravan routes through Batang (Paan) and Teko. Although the Chinese regard it as an inferior product, it is greatly esteemed by the Tibetans for its powerful flavor, which harmonizes particularly well with that of the rancid yak’s butter which they mix with their tea. Brick tea comprises not only what we call tea leaves, but also the coarser leaves and some of the twigs of the shrub, as well as the leaves and fruit of other plants and trees (the alder, for instance). This amalgam is steamed, weighed, and compressed into hard bricks, which are packed up in coarse matting in subunits of four. These rectangular parcels weigh between twenty-two and twenty-six pounds—the quality of the tea makes a slight difference to the weight—and are carried to Kangting by coolies. A long string of them, moving slowly under their monstrous burdens of tea, was a familiar sight along the road I followed.[2]

The brick tea is packaged [in Kangting] either in the courtyard or in the street outside, and it is quite a complicated process. When the coolies bring it in from Ya’an, it has to be repacked before being consigned upcountry, for in a coolie’s load the standard subunit is four bricks lashed together, and these would be the wrong shape for animal transport. So they are first cut in two, then put together in lots of three, leaving what they call a gam, which is half a yak’s load. Tea which is going to be consumed reasonably soon is done up in a loose case of matting, but the gams, which are bound for remote destinations, perhaps even for Lhasa, are sewn up in yakhides. These hides are not tanned but are merely dried in the sun; when used for packing they are soaked in water to make them pliable and then sewn very tightly around the load, and when they dry out again the tea is enclosed in a container which is as hard as wood and is completely unaffected by rain, hard knocks, or immersion in streams. The Tibetan packers are a special guild of craftsmen, readily identifiable by the powerful aroma of untanned leather which they exude.

Another prominent guild in Kangting is that of the women tea coolies who shift the stuff from the warehouses to the inns where the caravans start. They have a monopoly on this work and the cheerful gangs of girls are a picturesque element in the city’s life. They need to be immensely strong to do a job which consists of carrying over a short distance anything up to an entire yak’s load several times a day. Many of them are quite pretty (and well aware of the fact); they look very gay and rather brazen as, giggling and chattering among themselves, they move along with their heavy burdens, which are held in place by a woolen girdle around the chest.[3]

So brick tea has a very long history in China. This doesn’t really enlighten me about tea in Korea very much, but it is interesting to me just the same. The Osullooc tea plantation has only been in business since 1979. So it doesn’t have a long history in itself, but uses the long historical aspects of tea in all it’s advertising. The tea plantations are all certified organic, so that is a very good place to start.

I can say that post fermented tea is an acquired taste. The Osulloc company make many claims for the tea. A particular selling point is the clean environment of the island, but they also make special mention of the long, post-fermentation aspect of the curing process. They claim that they use the long and ancient history of Koreas skills in fermentation. As ‘fermentation’ is the current buzz word in culinary circles, I’m just a little bit suspicious, But that’s me. They also claim to use traditional Korean fermented pastes. I don’t know what these are, and they are not saying, it’s certainly not Kim Che.

I can’t say either way, as to whether it is good for you or not, but it has a unique quality. I think that it would possibly be a good bed time tea, as it is low in stimulants and that could be good? I’m certainly impressed with the effort that has gone into the presentation, pity it will all be thrown away! Maybe if they could develop a special paper made out of tea leaves, then we could infuse the wrapping as well, still have a great ‘cuppa’ and reduce waste?

Looking at all the effort that has gone into the presentation and advertising, I think that it just might be a triumph of style over substance.

Maybe it will help me sleep better?

Unfortunately, that isn’t one of their claims!

We enjoy our tea from a Gwyn Hansen Piggott tea pot with matching cup and saucer.

- [2] Migot, André (1955). Tibetan Marches. Translated by Peter Fleming. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., U.S.A., pp. 59-60.

- [3] Jump up ^ Migot, André (1955). Tibetan Marches. Translated by Peter Fleming. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., U.S.A., pp. 83-84.

.

.

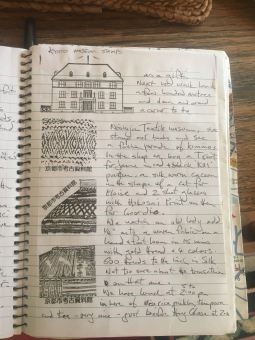

Namikawa Yasuyuki was a very famous Cloisonné artist who lived and worked in Kyoto from 1868 to 1926. His museum is in his old house and is of the old-fashioned Kyoto style called ‘machiya’ . Namikawa became very wealthy from his work as he invented new styles of working and new techniques. I’m not particularly interested in Cloisonné, but I’m very impressed by the technical genius and level of skill. It’s hard to believe that this level of fine detail could have been achieved prior to the invention of oxy torches, plasma cutting and tig welding. As it turns out Namikawa didn’t actually do the manual work. He just designed it. He had a righthand man called Nakahara Tessen. He was the real genius! But as with all things, it’s a union that makes for a greater whole.

Namikawa Yasuyuki was a very famous Cloisonné artist who lived and worked in Kyoto from 1868 to 1926. His museum is in his old house and is of the old-fashioned Kyoto style called ‘machiya’ . Namikawa became very wealthy from his work as he invented new styles of working and new techniques. I’m not particularly interested in Cloisonné, but I’m very impressed by the technical genius and level of skill. It’s hard to believe that this level of fine detail could have been achieved prior to the invention of oxy torches, plasma cutting and tig welding. As it turns out Namikawa didn’t actually do the manual work. He just designed it. He had a righthand man called Nakahara Tessen. He was the real genius! But as with all things, it’s a union that makes for a greater whole.

You must be logged in to post a comment.