After the successful firing of my kiln, which could have been better, but served well as a proof of concept firing. I have a couple of other jobs lined up while I’m in Korea. One of them was for an institution, but the person in charge hadn’t applied for permission to build a kiln there until last week, so no permission was forthcoming – at least not in time. I couldn’t build a kiln in an institution without permission, just in case it was refused, or so slow in coming that it would be approved for the next financial year, either way. I wouldn’t be able to get paid for any work done now. So I decided to move on to the next job.

One of the potters working on the big kiln in Bangsan Porcelain Village, named Mr Kim tells me that he has built a downdraught firebox wood kiln at this home on the east coast, but it didn’t work all that well. We have been discussing this over dinner in the evenings. I show him my plans for the Bangsan kiln and all the mathematics that I use to work out all the dimensions for the various openings, firebox, flues, throat and chimney etc. He asks me to come with him after this job here is over, he’ll drive me to his place and I can look at his kiln and make any suggestions that I can think of to help him improve it. He tells me that he’ll drive me back again afterwards as well. This is good news, as my suitcase is now approaching 30 kgs with the load of sericite stones that I have recently added to it. Catching public transport is a bit of an ordeal with such a heavy bag. I decide to go through it and jettison everything that is not essential. I get rid of 5 kgs in that effort.

We set off to cross the country, over the mountain range that runs down this part of South Korea. We stop at a famous lookout to view back to where we have just come.

I look over the edge of the viewing deck and unsettlingly, I can see what appears to be the previous wooden deck that has collapsed into the ravine below us!

The trip is several hours to the East Coast and it turns out that Mr Kim owns a hotel and restaurant on the top of a cliff over-looking the sea. He tells me that I can stay in one of the empty rooms for the next few days while he shows me around. We dine in the restaurant run by his daughter and son-in-law and the next day at dawn we are off for a walk down to the harbour to see the sun rise.

After our walk, mr Kim takes me to the local fish markets, where we buy fish, tofu, vegetables, chillies and pickles for the restaurant.

If you ever think that you might need 20 kgs of dried chillis. I know where to get it.

Mr Kim tells me that he built the hotel 20 years ago, and moved his growing family here from their first home that he built up in the mountains an hour inland from here. He studied architecture and engineering at university and set up his practice high in the mountains where they were snowed in for 3 months of the year. It is a very old subsistence farming area with a lot of ’National Trust’ Listed and preserved farm buildings that date back hundreds of years. These old farm houses were preserved because the climate is so difficult up there, no one could be bothered to pull them down and rebuild on the site. Mr Kim operated his practice during the winter lock-down through the internet. Korea has really excellent internet coverage and speeds. He and his wife raised 3 children up there. He tells me that he will take me up there to see the old place. He still owns it. He tells me to bring a jacket.

We drive up the narrow, winding, mountain roads full of mist and fog, the air is getting colder. I can feel the chill in the air deepen. I’m glad that he warned me to bring a jacket. We drive for an hour or so until we crest one of the mountain peaks and discover a clearing with a very ancient farm house on it. There are row upon row of stone buttressed retaining walls to make garden beds on the steep hilly terrain. Generations of farmers have toiled here in this soil, so high up on this mountain. I can feel the aches and pains of all this endeavour, solidly secreted in this soil, and in these terraces.

The old house is a combination of earth and timber. The roof is made of timber shingles that have been split from massive slabs of wood. It’s a beautiful old farm house.

We drive on over the next hill and come to a stop in the narrow street. He hops out and ushers me across a narrow little bridge over a torrent and into a grassy clearing between a few old hexagonal pavilions. There are row upon row of old ongi jars lined up around the edges of the grassy clearing. It hasn’t been mowed for some time and everything is quite derelict looking – but very familiar.

I’m struck by an intense feeling of deja vu!

I turn to him and say the strangest thing. “I’ve been here before”. I’ve lived here! Actually, I’ve slept in that building over there and had a meal in that building there!”

It’s so unbelievable. I can’t believe it. At first, I’m not even sure if what is coming out of my mouth somewhat unintentionally is really true, but the more that I look and take it all in, the more that I’m sure. Yes. I’ve stayed here! But this place is so remote! It’s almost impossible!

Mr Kim is taken aback. His eyes are wide. He is shocked at what I’m saying, and so am I, Because it couldn’t possibly be true. Am I just joking?

Is there some sort of lost-in-translation effect happening? He doesn’t believe me. He tells me “No one comes up here. There is nothing here. Most of these farms are abandoned. How could it be?”

I’m perfectly sure of it now, as I look around and take in more of the details, it is all coming back to me. Yes! I’ve stayed here 8 years ago! Mr Kim looks puzzled, then his face lights up. “Yes, of course. I let a young potter live here 8 years ago rent free, if he rebuilt my wood fired kiln for me in lue of rent.” He was Mr Jaeyong Yi!

When I came to Korea for the first time in 2016, my translator, guide and driver. Ms Kang SangHee drove me up here from Cheongsong way down south. We were on a mission to find ancient sites where sericite porcelain was first developed. I had met Mr Jaeyong Yi down there in Cheongsong. He had invited us to stay with him in his house, in the mountains, as it was on our way to Taebaek up north to visit another sericite location. I wrote all about that adventure up here in Taebaek, back then in my first Korean blog,

’The Kim Chi Chronicles – part 3, 16/9/16 on <’tonightmyfingerssmellofgarlic.com’>

Mr Jaeyong Yi was most hospitable and looked after us very well at that time. The grounds are not as well kept anymore, now that no one lives here. But it still has a charm about it.

We walk around and laugh at the impossibility of it all and the absurdities of life.

Our next stop is to drive down the coast for another hour farther south to catch up with an old friend that we both know. HyeJin Jeon, was a PhD student in the Yanggu Porcelain Research Centre in Bangsan some 6 or 7 years ago. I bumped into her a couple of times on different trips to Korea during her studies there. We became friends and kept in touch by email over the years. She graduated with her PhD a few years ago, and has recently been appointed as the Professor of Ceramics at the Gangneung University on the East Coast. Its not that far further south from where we are.

HyeJin Jeon is very pleased to see us and gives me a big hug. It’s been 6 years since I last saw her in Bangsan.

She shows us around her faculty, then the three of us spend the day going around all the Museums and ancient buildings in Gangneung city. We stay on for dinner and drive home in the dark. It was very nice to catch up after so long. I’m pleased that she is doing well.

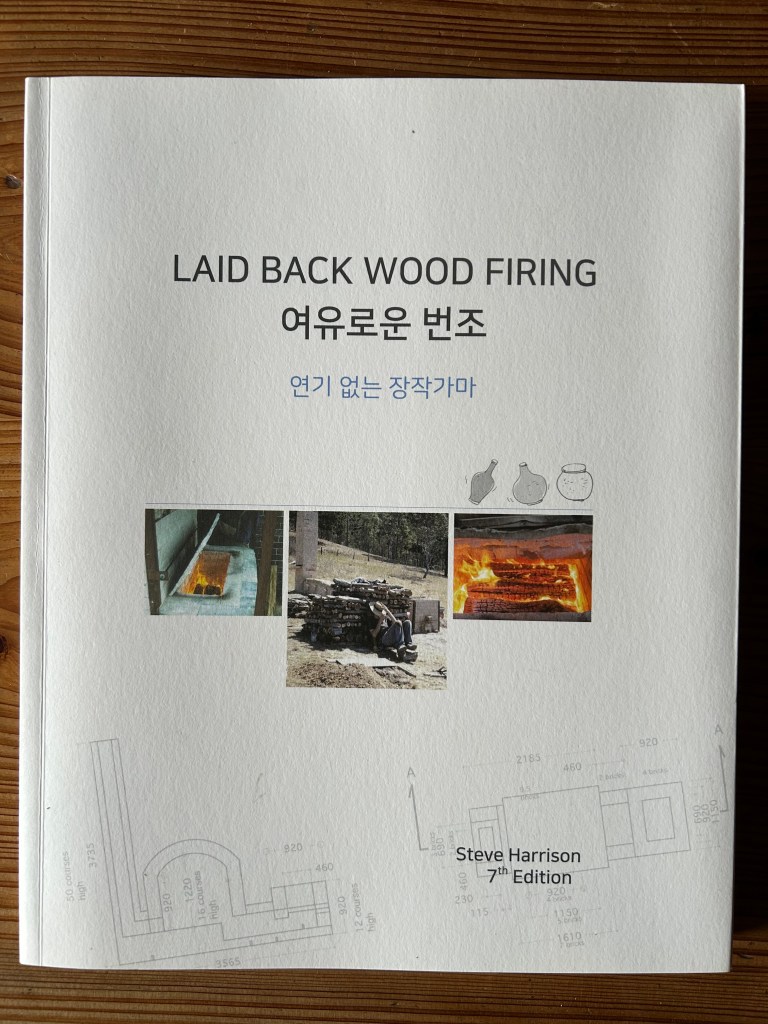

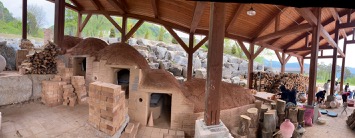

The next day, Mr Kim shows me his kiln, I go over it, I measure all of its critical features and then spend an hour drawing up a sketch and working out the exact proportions of its openings. I come to the conclusion that the flue needs to be bigger, much bigger. Bigger by 3 times! This is the major problem. But the fire box could also be larger again by half as well. These alterations wont be easy, but are doable. I also suggest that it might be better in the long run if he starts again from scratch. I give him the plans for my kiln that I built in Bangsan as a starting point to help him get the best outcome. He looks at my page of calculations and announces. “ You are not just an artist, you are a scientist!”

Instead of driving me back up to Bangsan, after some discussion, we decide that it will be best if Mr Kim drives me to the local station, so that I can catch a train across to Yeoju and visit both Mr Lee JunBeum and my old friend, former driver, translator and guide, Kang SangHee.

It’s good to see Ms Kang SangHee again too, I catch her taking my picture when I’m not looking, so I reciprocate.

We meet up in Mr Lee’s wife’s cafe and bakery, where Ms Kang is helping her bake the days bread.

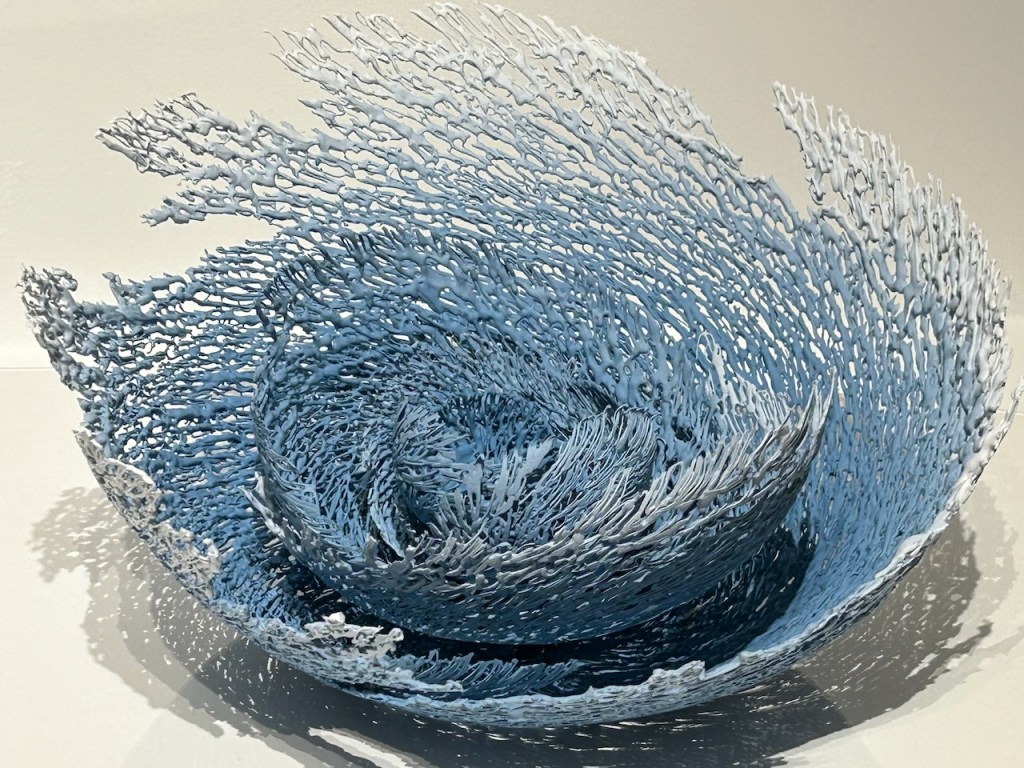

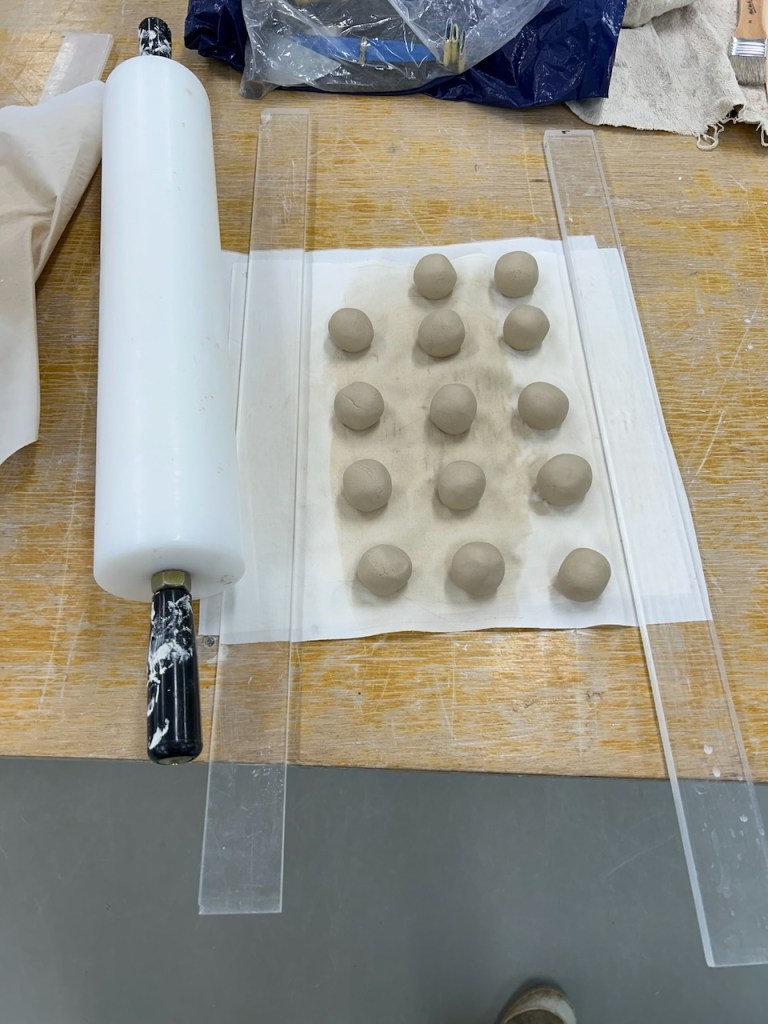

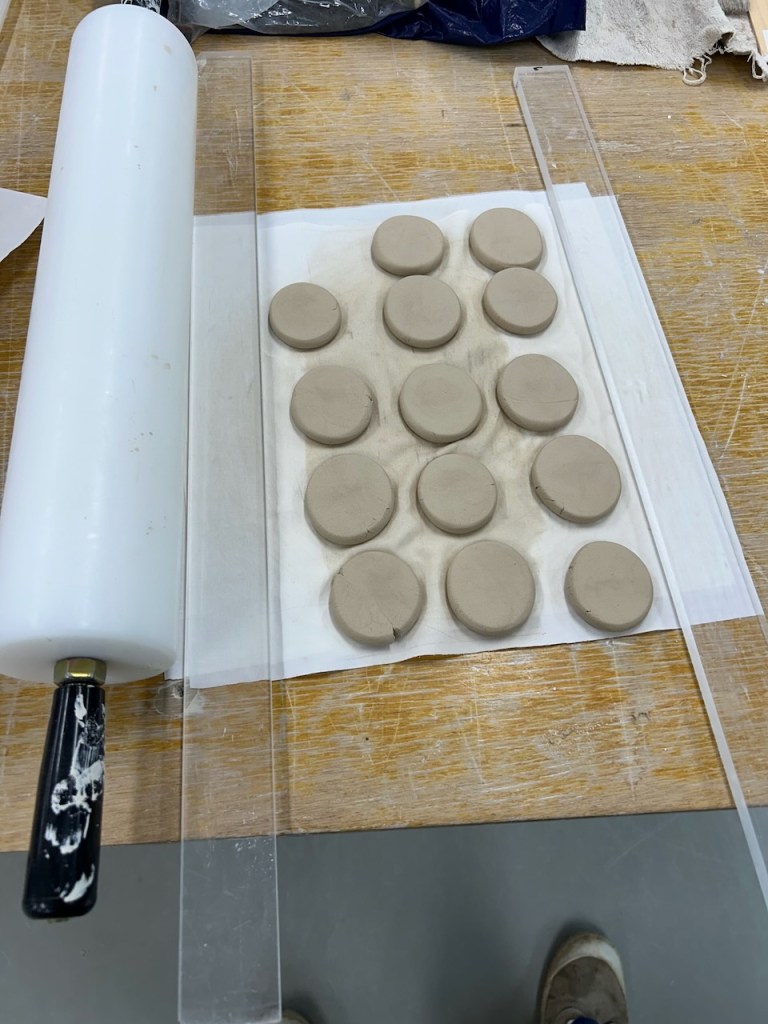

We spend the day travelling to all 3 sites of the ceramics Biennale. There are some very impressive ceramics on show. Later, I am able to help JunBeom with his new kiln. The least that I can do to show my appreciation for all his help.

The next day JunBeom and Yoomi drive me to visit the National Treasure potter of traditional sgraffito slip decoration, called Buncheong.

His name is Park Sang Jin and they get a long chat in Korean, insight into which I get through occasional translations from Jun Beom, then we all get a guided tour of his workshop, gallery and kilns.

On my last day in Korea we travel south to the city of Andong to visit the other Mr Kim, Kim SangGe, we worked closely together on the Bangsan kiln and he invited me to visit him if I was ever in Andong. He has an amazing roof structure over his workshop and kiln shed. Possibly cast concrete, but with a decorative layer of old weathered and broken roof tiles applied as a kind of mosaic. It’s really beautiful. Artists are just so imaginative and creative in everything that they do. I wish that I’d thought of doing that! Mind you, I don’t have access to thousands of old weathered and broken roof tiles, nor the funds to have an undulating concrete roof cast in-situ. Not the sort of thing that I could ever own, but I’m very pleased to be able to visit.

Mr Kim Sang Ge, serves us a special tea made from dried Tibetan chrysanthemum flowers. Interesting, but not particularly flavourful or tasty. He asks if I like it, and I reply yes – just to be polite, what else can I say? He then gives me the whole packet. I thank him warmly, but I know that I can’t bring it back into Australia, so I give it to Jun Beom when we get home. It was very generous of him and I appreciate that.

Mr Kim led the kiln building team that built the 5 chamber kiln in Bangsan that Janine and I experienced firing back in April this year, see my blog entry; <Kiln Firing in KoreaPosted on 13/05/2024>

Mr Kim’s kiln is made from thousands of hand made cone shaped raw clay fire brick blocks to form the domes of each chamber, plus an equal number of rectangular blocks used for the walls.

Mr Kim takes us to see the spectacular fire ceremony that takes place this time each year as part of the Traditional Harvest Festival in Andong. There is a tiny traditional Hanok Village of small, earth and timber, thatched roofed buildings, set in the bend of a river, opposite some steep cliffs. it’s an idillic spot, exceptionally beautiful. Each year at this time the ancient founders of the village are remembered by hoisting ropes up across the river, over to the cliffs and hanging burning hand made flares made from leaves and twigs. The sparks flutter down from the ropes into the river in the night sky. It’s quite dramatic. There are no modern fireworks going ‘bang’! Just the gentle cascade of sparks down from the sky.

I’ve been so lucky to have been able to witness so many wonderful things on this trip. Not my usual artist in residence stay in just one place or a simple conference presentation. One of my planned kiln jobs evaporated, but was replaced with a multitude of very different experiences. I am very grateful to all my Korean friends! Thank you!

Nothing is perfect, nothing is ever finished, and nothing last forever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.