We have just completed the 2nd Moon Jar Making workshop, with the 3rd and last for this year going ahead next weekend. Great progress was made learning to throw and assemble the shapes that go to create a traditional, fully rounded, spherical shape pot on the potters wheel.

This morning our first job is to deal with a lot of fruit that has been falling off the trees during this last weekend of very hot weather.

Janine dealt with the peaches and I decided to juice the pears.

Summer is a busy time in the orchards and garden. Inadvertently, we grow more than we can eat in real time. so we cook, preserve, stew and bottle the excess, but also share the largess with the students that come to the workshops and give more away to our friends and neighbors.

I have a few people on my waiting list wanting to do a tool making workshop. If I can get two more takers, then it will go ahead on the 14th of March. Please reply if you are interested. Otherwise it will roll over to next year.

Tomorrow, I’ll be making clay again, as these last couple of workshops and the one already booked out for next weekend, will pretty much exhaust most of my remaining stock of aged plastic clay.

One thing flows into another at this busy time of year. I went up to Sydney and bought a pallet of raw materials to enable me to keep making clay into the coming year. There is $1,000 worth of clay body material on that pallet. By the time that I’ve processed it, paying my self a very modest wage, my clay costs $2.50 per kilo. If I were to add on some sort of margin to allow for running a business, insurance, wear and tear, electricity etc. Then the clay would cost $4.00 a kilo. $40.00 for a 10kg bag. Which is more or less what you pay at the craft shop.

It seems like such a lot of money, but this is the reality of modern life and business. Things keep going up all the time. Janine and I live mostly in a fantasy world of our own creation. Being so self sufficient and self reliant here, it’s easy to loose track of the price of things. The once a year purchase of materials, like this, apart from being shocked by the price, it is also a lesson in international trade and the actions of multi-national corporations’ cut throat policies.

Ceramic materials that were once readily available locally, have nearly all been bought-out and closed down, with imported similar materials brought in to replace them, always from the 3rd world. I have to keep testing the new stuff to make sure what it is that I’m getting. You can’t just expect to do a simple substitution in your old recipe. I try very hard to use Australian raw materials for my workshop clay body. I buy in clays from Victoria, Southern NSW and Queensland to get a reliable consistent mix that is sufficiently plastic for wheel work. Regrettably, the fantastic plastic secondary kaolins from Gulgong are no longer mined. They are still there under the ground. But the sites are all locked up and then imported, very much more expensive materials are offered in their place. I used to buy the Gulgong kaolins at $400 a tonne. Now I’m asked to pay $100 for a 25 kg bag of the American kaolin that is the new substituted material. I don’t buy it. That’s a 10 times increase in price.

After tomorrows clay making session. I will have made up, mixed and twice pugged 2,000 kilos (2 tonnes) of clay in the past 12 months – and then given most of it away! Because I don’t charge for clay at my workshops, but I’m thinking that I might have to start. Maybe – First bag free, then $20 per pack after that?

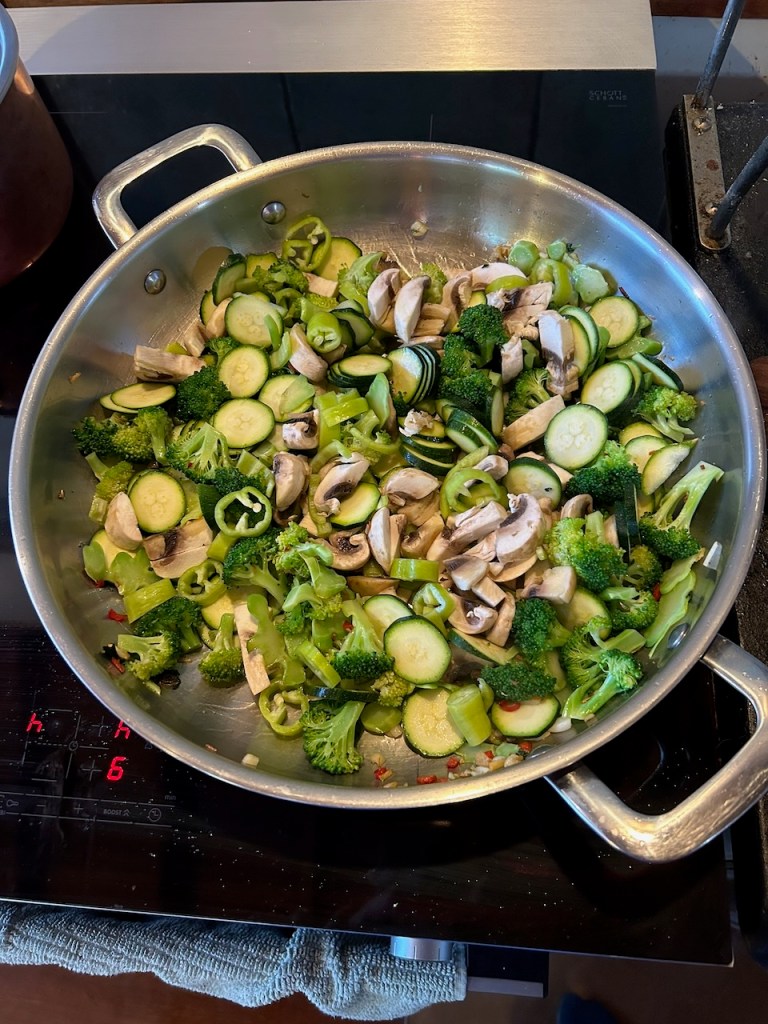

I go into town once a week to do some shopping, mostly to buy protein. Usually milk, fish, tofu and then sometimes either chicken or pork. Always organic and free range where that is an option. It is the most expensive part of any meal, but we buy very little of it. Everything else we manage to do for our selves. We make do with what we can grow. This leads to a bit of monotony at times, so I put a bit of effort into varying our meals. At this time of year, every meal is a variation on ratatouille. Tomatoes, egg plant, capsicum, zucchini, broccoli and celery. I have to mix it up a bit, one night with tomato, the next without, sometimes with tofu, another night with mushrooms. Always with fresh garden herbs, which at this time of year nearly always includes either sweet basil or pesto, but I keep it varied, sometimes with a Thai basil, coriander, lemon grass and lime juice with fish sauce. Another time with Middle Eastern spices. The next with an East Asian flavour of oyster sauce, fresh ginger, always with loads of garlic and alternately fried off good olive oil or sesame oil.

There is always something going on here. We seem to be able to keep ourselves busy.

I’m keen to pass on some of the skills that I have learnt over my life. There is more or less nil ceramic technical skills content being taught in the few remaining ceramic courses being offered here these days. It’s all part of the lobotomisation of education, combined with the enshitification of everything else.

We offer a brief, small, quiet experience of information/skills transfer in a creative environment. It’s a beautiful learning space, well lit and airy. I like to tell myself that the staff are alright too!

Nothing is ever finished, nothing is perfect and nothing lasts.

Enjoy the moment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.