I’m working in Korea in this little artists village community on the edge of a country town. There have been potters here making and mining porcelain stone for 800 years. The village is located away from the township, such that the smoke from the traditional wood fired kilns is not a concern for the township residents. It was great forethought in its time to start to locate all the wood kilns up into this side valley.

But it doesn’t stop there, this has been a long-term plan and as with all long-term plans, it is evolving and adapting with current thinking and social mores. Hence my involvement here with the constriction of my low-emissions wood kiln firing designs and techniques. I was commissioned to start this work here, back in 2019, I was all set to come, but before I could start, we had the fire, then covid intervened. So I was unavailable for some years. But I’m back here again now the the plan is back on track.

My demonstration firing was very successful. In previous firings here the only fuel available to fire the kilns with was very dry 5 year aged local pine. The standard fuel here that everybody uses. It is a statement of fact here that dry pine is the only fuel that works in a kiln!

Last year when I was travelling around, I visited a famous potter’s studio, where they fired with wood. He had built a special pine fuel drying kiln, to desiccate his very thinly split fuel. He told me that it was his special secret, and that only desiccated pine could raise the temperature of the kiln easily. Other potters struggle with ordinary wood, but he had discovered the answer. I decided not to mention that I sometime throw water over the dry pine to get a better result! He had no concerns about making smoke. That was taken as a norm. All kilns make smoke, don’t they!

In the kilns that I have built here, the 5 year seasoned pine burnt furiously and it was very difficult for me to minimise the smoke. I managed it, but wasn’t at all happy with such dry volatile fuel. I enquired about alternatives. There is hard wood available in the form of oak and acacia. But no one uses it for kiln firing as it doesn’t work!!! That was the local opinion anyway! Meaning that it doesn’t work in the traditional kiln designs, used here, using traditional techniques. I thought that it might just be ideal for my purposes, for use in the down draught firebox.

For this most recent firing I had requested that both pine and oak be available, to give me options. There is also the possibility of using local acacia wood, But I was told that this is not considered be be a useful fuel for kilns. That made me more interested in trying it out. I said that it is one of the better fuels back in Australia, but that hasn’t cut any ice here as yet – apparently.

When I arrived, the oak and pine were stacked neatly in front of the kiln. A lovely sight. I started by using just 100% oak. Initially, I found that the oak burnt black and then smouldered. Just as everyone else had found. But I was perfectly sanguine about this, because my local stringy bark timber back in Australia does the same. In fact the locals wouldn’t cut it for use in their open fire places because of this. I quickly found that a blend of 80% oak with 20% pine was a good combination to get started with, using the flashy pine to keep the oak burning. This combo worked well from 700 up to about 1000 oC, when I cut the use of the pine back to just 10%, and finally at 1100oC, I was using straight oak.

This series of combinations got the kiln firing well, while still burning quite cleanly with almost non-existent traces of smoke from the chimney. Just the occasional waft of pale grey smoke.

Problem solved. I was able to fire up to cone 9 in reduction with virtually NO smoke, while firing in reduction. This is a notable achievement here. A lot of chatter and comment, firing in a wood fired kiln with no smoke, by using the oft’ maligned local oak. Applause all round. Who’d have thought?

Maybe the local acacia might even have been better? But that is a project for another visit.

There are two ceramic university campuses that are keen to follow up on this, as they are located in cities, and there is no possibility of being able to make smoke in their location. Downdraught oak firing might just do the trick.

Word gets about it seems. During the cooling period I got news that the opening of the kiln would have to be delayed from one day to the next, then from the morning of the appointed day, to the afternoon, as the Federal Minister of Culture wanted to be there to see the results unpacked, and he could only be available in the afternoon of the 8th. So when in Rome… I delayed the opening at his masters pleasure.

I’m certain that this is no accident. Of course, I don’t know, but it smacks of ‘realpolitik’ strategising. I’d bet that the Director of the Museum has organised this as a media event to promote the Museum. Politicians fund the things that they see, are involved in, understand, AND if it looks like a successful vehicle to advantage their own career. They want to be seen associated with it.

Just a thought! Call me cynical! But…

I remember some years ago. I collected some porcelain stone from here and took them back to Australia and made a large bowl out of them. I glazed the bowl with a subtle blue celadon glaze that I made incorporating kangaroo ash. A kangaroo had died on my property, so I calcined it and retrieved the local source of phosphorous from the bones. Phosphorous is known to enhance the optical blue in certain pale iron glazes like celadon.

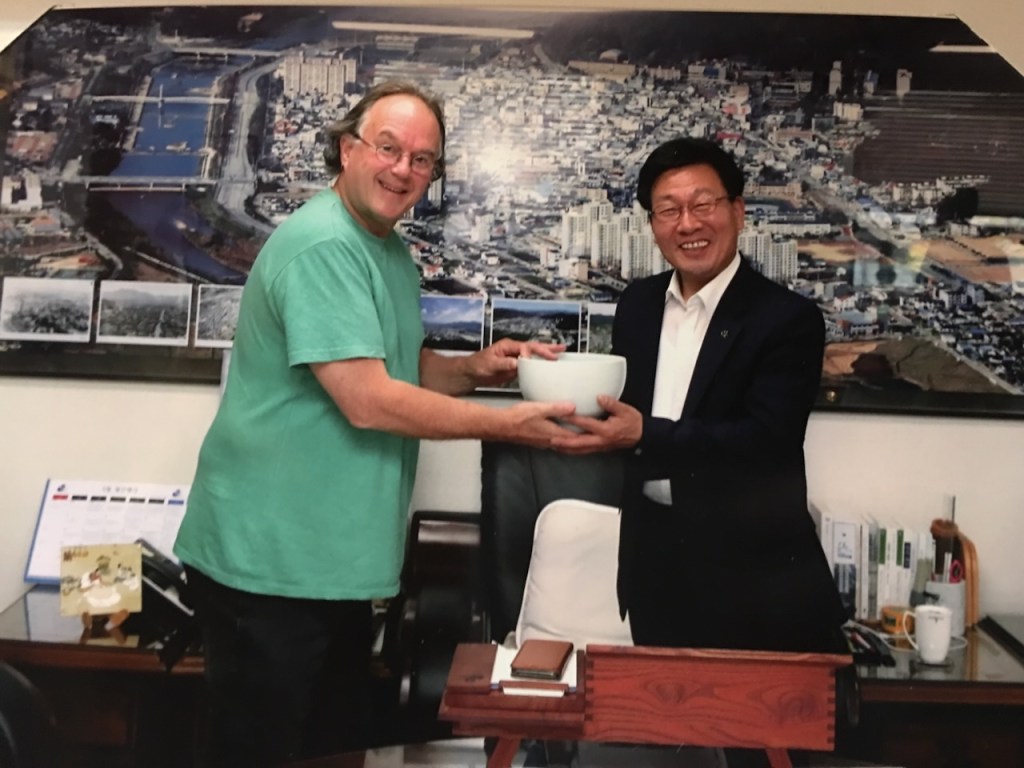

I gave it as a gift to the Museum Director along with the story. This was my own private Cultural Exchange project. His Korean stones collected from this historic site, made into a pure sericite clay body glazed with my Australian kangaroo blue glaze. He loved it. He was so taken by it that he called the Premier and made an appointment for us to meet him and make the bowl a gift to him. Thus bringing the Museum into his field of vision.

We turned up just before the appointed time for our 15 mins of fame, and were eventually ushered into the Official Office along with newspaper reporters, translators, aids and other staff. I was duly introduced to the Premier, a little bit of small talk. He had been very well briefed and made appropriate comments. Then it was down to brass tacks. I handed over the bowl and he graciously accepted it on behalf of the Korean People. He said straight away that he knew next to nothing of Ceramics, but understood the significance of the effort that had gone into such an art work and its cultural exchange significance. He thanked me again and shook my hand. There was a flurry of flash bulbs going off to record this staged event.

He asked me how I came to be researching Korean Porcelain from this remote place. I replied that Korean porcelain is unique in the history of world ceramics. I came here because of the history of the place and the pots that were made here. You can only learn so much from books. I had to come to experience it. He smiled, so you knew about Korean porcelain from back in Australia? I said yes, once I learnt about it, I had to come. The Porcelain Museum here is one of the very few places in the world where this kind of study can take place. Mr Jung, The Director, is very supportive, open and inclusive. He runs a great institution.

The Premier was reflective for a second, then said. I believe that you can build pottery kilns that fire with wood and make no smoke. This is important for the environment. Mr Jung has asked me for more funding for this kind of project. If the Museum is so famous internationally, attracting research like yours,

I will fund it!

The next day, the newspapers had the Premier on the front page announcing the success of his funding initiative for his international artistic ceramic exchange program, for the very successful, now internationally recognised, Yanggu Porcelain Museum. Every one wins. The Premier gets all the credit and is in the paper looking like a hero. The Museum Director got his funding. I enjoyed the research and achievement of making the lovely bowl. The premier mentioned before we all left, that the best place to keep such a unique bowl, would be in the porcelain museum.

Back to the present time and hence the sudden flush of offers of work to build similar such kilns from established potters and university campuses. Once it is shown to work, it gets it’s own legs. Word travels fast. These days it travels electronically with likes and re-postings. It’s very fast.

The Minister of Culture is coming for a visit to the Museum and will be at the opening of the kiln. The kiln has cooled more than enough waiting for him to arrive. I’m introduced to the minister, he asks me in Korean – if I can speak Korean. I recognise the phrase, so I’m onto it, but my recall of Korean standard reply phrases is so slow, that before I can make my clumsy reply, he already knows my answer, so swiftly continues in English. “So we will have to speak in English then!”. I nod my thanks.

We make some small talk. He’s been briefed on hisc way here about the nature of the project and asks me if it is going well and I reply yes. That’s the depth of our interaction. That was my 15 seconds of fame! The photographers elbow in and I’m shifted sideways. The minister looks quizzically at the kiln and my Jung explains something in Korean. The Museum team are then given the go-ahead to unpack the kiln.

The firing is unpacked and everyone ‘oohs’ and ‘arrhs’, the other potters here each look in and turn to me with BIG smiles and thumbs-up. Huge sigh of relief. Everyone is all smiles. The pots are mostly well fired, but I’m interested in the minutiae of the detail. I’m looking not just for colour, but for the depth of colour in the celadons. Not just a shiny surface, but a certain quality of soft melt and satiny quality there. I want to get in and see the flame path and the flashing on the exposed surfaces and kiln shelves. Where is the ash deposit and how has it melted. None of this is possible with 50 people crowding around and flash guns going off.

Its a bit like a crime scene or perhaps an archaeological dig. You don’t want a rabble of untrained people trampling all the evidence and the details. Just like an aboriginal tracker, I want to read the ephemera, the subtle traces and shadows, but that isn’t going to happen. The pots are whipped out and shown to the Minister, with total disregard of their place in the kiln and their fire face and lee side qualities.

It’s just a little bit of a shame, as I’d like to learn more than I am able to in this situation. Looks like I’m the only one who isn’t ecstatic! I am really pleased that everyone else is so happy with the result, but I know that I can do better. But I need to read the surfaces to be able to learn what I need to be better at it the next time round.

In a perfect world, I’d like to go slowly and examine each pot in detail. These pots aren’t just trophies and trinkets, they are also part of my research, or at least they were when they went in! But this has become a media event now, and that is also very important, possibly more important, because it may well result in continued or even better funding into the future. A topic far more important than one firing and a few glazed pots.

The firing is a success, no doubts. Everyone is happy. They all leave feeling uplifted and maybe just a little bit happy and warm inside to know that they have been somewhere where there is some sort of mysterious, but positive, environmental action taking place. Even though they don’t understand what it is.

Back at the Museum tomorrow, I’ll have to have a quiet look at all the work as we are setting up the show. But the exact context will be lost, however, I can fill in some of the missing info using my experience. I’m so pleased that everyone is happy, but I could have learnt more to help them with the next firing, as the kiln still needs some fine tuning.

What I could see quite clearly, was that the oak ash was very refractory. I’m guessing that it is very high in SiO2. We may need to burn a bit more pine in the mix to introduce some CaO (calcium flux) into the eutectic to get a softer surface from the ash deposit. I was burning 20% pine in the early stages without smoke. I might have to keep that up for the whole firing? As pine ash has a lot of calcium in it.

All grist for the mill in the future. I could also see that the floor at the back was still a little bit under-fired, so I was up at 5,30 this morning and went down to the kiln and took out the bag wall and rebuilt it one layer lower and with one full brick removed, to make larger gaps. I will see how this works after the next firing. I also placed one brick in the middle flue hole to force the flame out to the corners more. All little fine adjustments that I hope will make it fire more evenly.

Another option for the refractory silicious ash problem might be to place a few tiny pre-fired stoneware cups containing a spoon full of Na2CO3 (washing soda) in the front of the kiln. This will mimic a few years of charcoal built-up and decomposition at high temperatures, where sodium vapours are released from the burning embers. The soda will sublimate and slowly volatilise throughout the firing, reacting with the silicious ash as it is being laid down and help it to melt. or I hope so anyway. Everything is an experiment!

I could also use common salt to get a similar effect, but sodium chloride creates a slightly different look. I don’t want to change the look of the ceramic surface from wood fired into salt glaze pots. But anything and everything is worth a try. At least once. I first came across this light salting technique being used in La Bourne in France, back in 1974, where they had been doing it for centuries. As a naive student, I thought that it was a very clever idea that I hadn’t come across before. Many potters have used it since. In fact, it has become part of the standard repertoire.

With the influence of the Minister of Culture on the front pages and the release of the TV doco soon, there will almost certainly be more enquiries about this firing method. It is my intension to try and leave the kilns here in good condition and with useful, technically accurate kiln firing logs that the students here can use to do their own firings in the future. Hopefully we can work together ‘virtually’ via ‘Kakao’ talk or Zoom to achieve the best result possible. It could be a whole lot easier if they would just read the book, or at least the first chapter on how to fire!

All that is required now is for some young enterprising Korean potter to pick it up and run with it, develop a small business building these kilns for whoever wants one.

Maybe firing a downdraught fire box kiln with local oak will become a thing? I have shown that it is possible. It is now one other possible strategy for potters and academics in the field, to follow to be able to keep on wood firing here into a cleaner, carbon constrained, and environmentally friendlier future.

All I need to do now is to introduce them to the concept of the after-burner/scrubber to minimise PM 2.5 particulates, not just smoke. But that is a bridge too far at this time and for this visit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.